Death and the Compass is perhaps the most ambitious tale in Part II of Ficciones. It is, in the way that many of Borges’ stories have been, a detective story. The story follows Erik Lonnrot as he investigates the eerily occult death of Dr. Marcel Yarmolinsky. At the scene of the crime, Lonnrot discovers a piece of paper typewritten with the phrase “The first letter of the Name has been spoken”.

Borges indulges in a dazzling and difficult array of cultural, literary, and historical references. The long and short of it is that Lonnrot comes to believe that the occult phrase is an oblique reference to the unspeakable Hundredth Name of God. This instinct seems borne out by occurrence of a second murder, that of Daniel Simon Azevedo. Above the body, written on the wall in chalk, Lonnrot finds the phrase “The second letter of the Name has been spoken.” A third murder occurs, and another message appears on the wall. “The last of the letters of the Name has been spoken.” These murders form an equilateral ‘mystic’ triangle, which convinces Lonnrot’s colleagues that the murderer, motivated by occult purposes, has finished his spree. Lonnrot is not convinced. He believes that there will be a fourth murder – creating a diamond that will echo the number of the letters in the Tetragrammaton – the holy Name of God. He projects the location from the other three points and makes his way there on the appointed date at a strange house called Triste-le-Roy.

It’s a set-up. A criminal named Red Scharlach is there waiting for Lönnrot to arrive. Scharlach explains that the first murder (Yarmolinsky) was an accident, but once Lönnrot got involved, Scharlach saw a way to lure Lönnrot to this exact place and exact his revenge for an incident three years ago in which Lönnrot imprisoned Scharlach’s brother and shot Scharlach. Scharlach, in parallel, shoots Lönnrot. The story ends.

I want to preface my analysis by saying that this story is one of the most complex and strangely haunting in the collection. I’ve wrestled with this post for a week or two simply because I have been unable to convey the feeling of the story and don’t feel qualified to speculate too much about the deeper themes even on a second or third reading. I encourage you to read the story and experience for yourself. But, since I did say I’d comment on all of these, I’ll give it a shot.

The first thing that jumped out to me was the that this story presents itself as a self-fulfilling prophecy. The act of following the clues to the fourth murder is the very thing that results in the occurrence of the fourth murder. The paradox of the self fulfilling prophecy has fascinated me for years, and ties in beautifully with the rest of Borges’ themes through this collection. Here’s why: Robert K. Merton is the guy who formalized the definition of the self-fulfilling prophecy in a 1948 article in Antioch Review. He wrote –

“The self-fulfilling prophecy is, in the beginning, a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the original false conception come true. This specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error. For the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning.”

To phrase it another way, the self-fulfilling prophecy is a fiction that, through belief, creates itself or becomes true. This kind of paradox is prevalent in cultures worldwide, from the Greek tale of Oedipus to Shakespeare’s Macbeth to Star Wars’ Darth Vader. Each acted to prevent X while unknowingly creating the conditions that enabled X to occur. This is beautifully in line with Borges theme throughout Tlön, and The Circular Ruins, and The Approach to Al-Mutasim in which reality is created by unreality and belief. Borges is fascinated with exploring the ways in which reality is not quite so immutable as it initially seems to us.

The second thing that jumps out is the echoes of the previous story, Theme of the Traitor and Hero. That story contained many of the same self-fulfilling prophecy elements that this one did, but it also presented itself as a kind of platonic form – that the form of “traitor and hero” is repeated again and again through time as a higher order structure that shapes our experiential reality. We see this issue of forms dealt with a little at the end of Compass, when Lönnrot says –

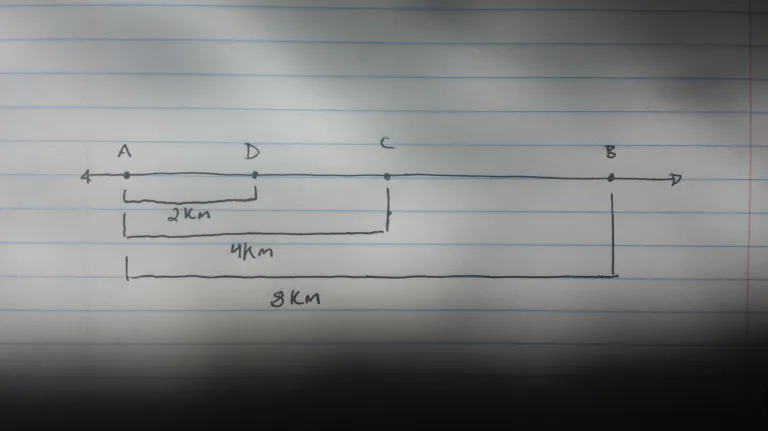

“In your labyrinth there are three lines too many,” he said at last. “I know of a Greek labyrinth which is a single straight line. Along this line so many philosophers have lost themselves that a mere detective might well do so too. Scharlach, when, in some other incarnation you hunt me, feign to commit (or do commit) a crime at A, then a second crime at B, eight kilometers from A, then a third crime at C, four kilometers from A and B, halfway enroute between the two. Wait for me later at D, two kilometers from A and C, halfway, once again, between both. Kill me at D, as you are now going to kill me at Triste-le-Roy. “

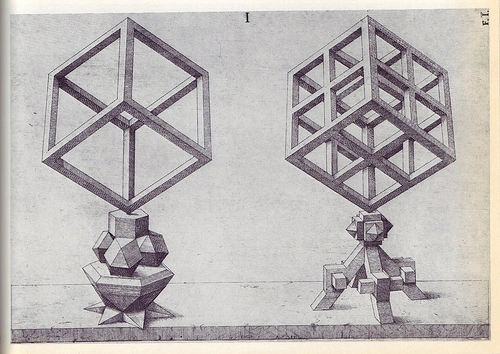

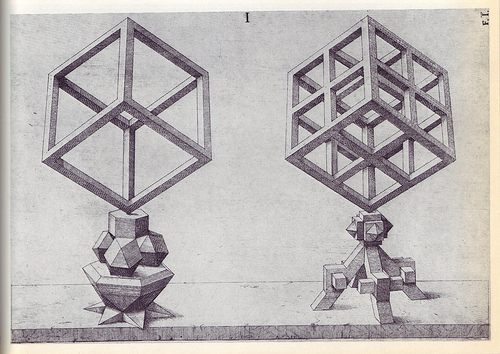

So while the theme of forms is reiterated here, we are given a glimpse into the plethora of forms that exist. Lönnrot suggests a different paradox, a different labyrinth, a different form for the next time this drama plays itself out. I drew a brief diagram to help visualize the preceding quote.

This is Zeno’s Paradox! Only reversed. I’m not sure what that means. Maybe Lönnrot is setting up another paradox. Scharlach can’t kill him at D after murders A, B, and C, because he will come to point D before he commits the murders at B and C. Or perhaps the idea is simply that Lönnrot is tired of the labyrinth, and is content to simply move from A to D, instead of moving from A to B to C to D all over again.

The last thing I felt like pointing out was the continuous use of the labyrinth, represented in the paradoxical forms and self-fulfilling prophecies, but also in the house Triste-le-Roy itself. This is some of the most beautiful language in the collection, and it would be a shame not to revel in it a little bit.

“Lönnrot advanced among the eucalypti, stepping amidst confused generations of rigid, broken leaves. Close up, the house on the estate of Triste-le-Roy was seen to abound in superfluous symmetries and in maniacal repetitions: a glacial Diana in one lugubrious niche was complemented by another Diana in another niche; one balcony was repeated by another balcony; double steps of stairs opened into a double balustrade. A two-faced Hermes cast a monstrous shadow.”

“Lönnrot avoided Scharlach’s eyes. He was looking at the trees and the sky divided into rhombs of Turgid yellow, green and red. He felt a little cold, and felt, too, an impersonal, almost anonymous sadness. It was already night; from the dusty garden arose the useless cry of a bird. For the last time, Lönnrot considered the problem of a symmetrical and periodic death.”

It’s an achingly, hauntingly beautiful and sad story. It is profoundly strange and enchantingly written. One of the hardest to write about for me, but one of my favorites.